Magazine

From source to tap - new EU drinking water directive commits the entire supply chain

All private and public institutions and companies that provide water for human consumption are subject to strict guidelines. These measures protect the public drinking water supply, which is part of the critical national infrastructure. Clean, high-quality and safe drinking water is therefore the declared goal of updated EU Directive 2020/21841. It came into force on 12 January 2021 and must be implemented by all member states within two years.

In addition to the defined responsibilities for water suppliers, a risk assessment for domestic installations has been added, which mainly concerns priority localities. The risk assessment is to be carried out through a Water Safety Plan (WSP), which allows for a preventive response to potentially hazardous events and for them to be monitored using a risk-based approach.

To protect water quality, several requirements are already legally binding for water suppliers in the European Union. In Germany, these include the Drinking Water Ordinance (TrinkwV)² and the guidelines for risk and crisis management DIN EN 15975-1³ and DIN EN 15975-24 drawn up by the DVGW (German Technical and Scientific Association for Gas and Water). In addition, all institutions and companies that provide water in any way must fundamentally ensure that they comply with the generally recognised rules of technology in the planning, construction and operation of facilities for the production, treatment and distribution of drinking water.5

Priority locations will bear more responsibility for clean drinking water in the future

The risk-based approach of EU Directive EU 2020/2184 contains three essential components (Art. 8-10)1 and concerns the entire supply chain up to the point of exit:

- Risk assessment and risk management of the catchment areas of sampling points in line with the guidelines and WSP manual of the World Health Organisation (WHO)

- Risk assessment and risk management of the supply system, i.e. the possibility for water suppliers to tailor monitoring to main risks and to take necessary measures to manage the identified risks (concerning extraction, treatment, storage and distribution of water)

- Risk assessment of domestic installations, i.e. potential hazards from domestic installations, such as legionella or lead

Since the quality of water depends not only on the precautionary measures taken by water suppliers, but also on the condition of the domestic installations through which the water is used for human consumption, this point has been explicitly included in the new EU directive. It is to be expected that a risk-based management system (e.g. a hazard analysis) will also be required by law for domestic installations in the future. This mainly affects priority locations such as hospitals, health care facilities, old people's homes, kindergartens and schools, but also locations where many people congregate and where they are exposed to potential water-bound risks, such as hotels, restaurants, sports and shopping centres.1

Potentially harmful contamination, such as that which can be caused by old lead pipes or construction work, but also contamination by pathogenic germs, such as Legionella or P. aeruginosa, which can arise and spread due to stagnation or temporary decommissioning, are among the most common water-bound pathogens. They are to be prevented through the targeted risk analysis and associated preventive measures. The risk-based management system also addresses the questions of what exactly can happen in the worst case scenario, what health risks are associated with each of these, how these risks can be controlled and how it can be ensured that these can also be remedied.

Implementation of the risk-based management system – the water safety plan as a “living” document

The approach of a water safety plan – regardless of its name – is to be understood as less of a plan and more of a preventive concept5 based on hazard analysis. It is clear that if you are not familiar with your own installations, you cannot derive any risks and corresponding processes from them. However, these are essential when drinking water hygiene is at risk, such as in the event of incidents due to contamination or the interruption of piped supplies. Once the WSP has been designed and linked to the corresponding responsibilities, it flows into day-to-day business in a planned manner as a living document. In the handbook for small water utilities, the Federal Environment Agency therefore also recommends that it should not be regarded as something “additional” but as a “sine qua non”, which should be sensibly integrated into existing organisational and operational processes.5

Planning pays off for everyone in the long term

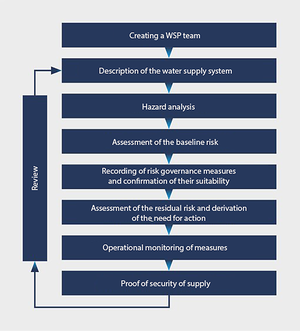

All thought processes and work steps of the entire water cycle that are necessary for security of supply, as set out in Figure 1, must be put in writing, the responsible persons defined and equipped with the corresponding competences and resources. This now also applies to domestic installations where there are specific risks to water quality and human health, especially – but not exclusively – in priority localities.

Figure 1: Tasks of the WSP approach at a glance5

Implemented sensibly, the WSP ensures safe, reliable, environmentally relevant and yet economical operation. The short- and long-term advantages of this quality assurance

- strengthen the organisational security of the company (supporting the management in the responsibility incumbent upon it and the care required to this end),

- strengthen the understanding of the water supply system among those responsible as well as technical staff (targeted motivation to question traditional positions and habits and to overcome potential operational blindness),

- draw the focus of operational attention towards potential weaknesses in the supply system,

- support the technical management in systematising the operational processes,

- promote knowledge and, based on this, the implementation of the rules and regulations,

- identify the need for improvement and provide a professionally sound basis for decisions on necessary investments,

- bring together experts and promote cooperation and communication (internal and external) and

- serve the preservation and documentation of accumulated operational knowledge.6

Event-related and cyclical revisions ensure topicality

Every water safety plan must allow for a continuous exchange of information between the relevant authorities and the drinking water installation operator. In this context, the WSP, as an important working and communication tool, must be subject to regular reviews. This is especially true for priority locations such as hospitals, which are also subject to a health and safety plan. The WSP is an indispensable part of the health and safety plan. It is likewise subject to constant review and adaptation to changing circumstances. New scientific and technical findings or personnel changes that affect the responsibilities documented in the WSP must result in an update of the document. This is called an occasion-based audit. This is contrasted with a cyclical review, which checks at regular, firmly defined intervals whether the content requirements of the risk-based management system are still being met in order to permanently ensure drinking water quality.

--

1 Directive (EU) 2020/2184 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 December 2020 on the quality of water intended for human consumption (new version). eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/. Retrieved on 16/08/2021

² Ordinance on the quality of water intended for human consumption (Drinking Water Ordinance - TrinkwV). Federal Ministry of Justice and Consumer Protection (BfJV). www.gesetze-im-internet.de/trinkwv_2023/. Retrieved on 19/03/2024

³ Safety of drinking water supply - Guidelines for risk and crisis management - Part 1: Crisis management. DIN German Institute for Standardisation. 2016-03. www.dvgw-regelwerk.de/plus/. Retrieved on 16/08/2021

4 Safety of drinking water supply - Guidelines for risk and crisis management - Part 2: Risk management. DIN German Institute for Standardisation. 2013-12. www.dvgw-regelwerk.de/plus/. Retrieved on 16/08/2021

5 The water safety plan concept: a handbook for small water suppliers. Federal Environment Agency. 2017. www.umweltbundesamt.de/sites/default/files/medien/374/publikationen/wps-handbuch-web.pdf. Retrieved on 16/08/2021

6 Requirements on infection prevention in medical care of immunosuppressed patients. Recommendation of the Commission for Hospital Hygiene and Infection Prevention (KRINKO) at the Robert Koch Institute. Federal Health Gazette 2021, 64:232–264. www.rki.de/DE/Content/Infekt/Krankenhaushygiene/Kommission/Downloads/ Infektionspraevention_immunsupprimierte_Patienten.pdf?__blob=publicationFile. Retrieved on 16/08/2021